“An equation for me has no meaning unless it expresses a thought of God.” —- Srinivasa Ramanujan Iyengar (22 December 1887 – 26 April 1920)

Srinivasa Ramanujan was born on December 22, 1887 in the town of Erode, in Tamil Nadu, in the south east of India. His father was K. Srinivasa Iyengar, an accounting clerk for a clothing merchant. His mother was Komalatammal, who earned a small amount of money each month as a singer at the local temple.His family were Brahmins, the Hindu caste of priests and scholars. His mother ensured the boy was in tune with Brahmin traditions and culture. Although his family were high caste, they were very poor.

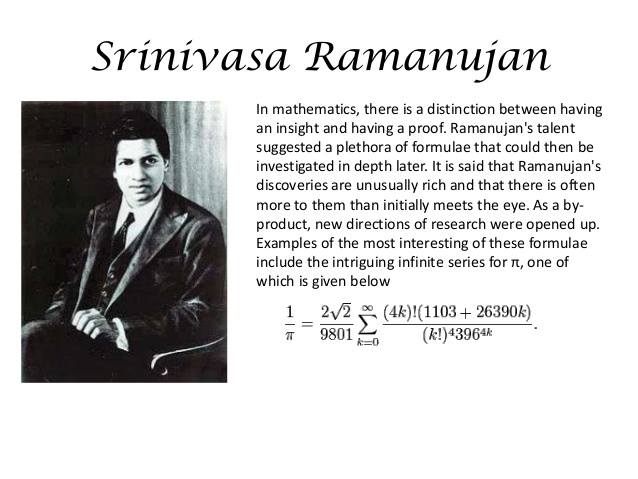

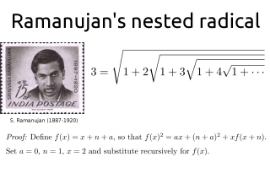

By the time he was 12, he had begun serious self-study of mathematics, working through arithmetic and geometric series and cubic equations. He discovered his own method of solving quadratic equations. As Ramanujan’s mathematical knowledge developed, his main source of inspiration and expertise became Synopsis of elementary results in pure mathematics by George S. Carr. This book presented a very large number of mathematical results – over 4000 theorems – but generally showed little working, cramming into its pages as many results as possible.

Ramanujan and his supporters contacted a number of British professors, but only one was receptive – an eminent pure mathematician at the University of Cambridge – Godfrey Harold Hardy, known to everyone as G. H. Hardy, who received a letter from Ramanujan in January 1913. By this time, Ramanujan had reached the age of 25.

Professor Hardy puzzled over the nine pages of mathematical notes Ramanujan had sent. They seemed rather incredible. Could it be that one of his colleagues was playing a trick on him? Hardy reviewed the papers with J. E. Littlewood, another eminent Cambridge mathematician, telling Littlewood they had been written by either a crank or a genius, but he wasn’t quite sure which. After spending two and a half hours poring over the outlandishly original work, the mathematicians came to a conclusion. They were looking at the papers of a mathematical genius. And G. H. Hardy had to say, “I had never seen anything in the least like them before. A single look at them is enough to show that they could only be written by a mathematician of the highest class. They must be true because, if they were not true, no one would have the imagination to invent them.”

Ramanujan arrived in Cambridge in April 1914, three months before the outbreak of World War 1. Within days he had begun work with Hardy and Littlewood. Two years later, he was awarded the equivalent of a Ph.D. for his work – a mere formality.

Now, let’s know what all time great mathematicians had to say with regard to this genius Indian Mathematician ::

“Suppose that we rate mathematicians on the basis of pure talent on a scale from 0 to 100. Hardy gave himself a score of 25, Littlewood 30, Hilbert 80 and Ramanujan 100.” — Paul Erdős, 1913 – 1996 Mathematician

“… each of the 24 modes in the Ramanujan function corresponds to a physical vibration of a string. Whenever the string executes its complex motions in space-time by splitting and recombining, a large number of highly sophisticated mathematical identities must be satisfied. These are precisely the mathematical identities discovered by Ramanujan.”

— Michio Kaku, Born 1947 Theoretical Physicist

“That was the wonderful thing about Ramanujan. He discovered so much, and yet he left so much more in his garden for other people to discover.” — Freeman Dyson, Born 1923 Mathematician and Physicist.

Wish you a happy National Mathematics Day to all my Indian friends and a great pleasure to share my happiness to all around the world. Mathematically yours.

–Hindol Mukherjee

iForindian©